“A map maker takes a messy, round world and puts it neat and flat on the wall in front of you. And to do this a mapmaker must decide which distortions, which faulty perceptions he can live with – to achieve a map which suits his purposes. He must commit to viewing it from only one angle.”

~Jody, Lonely Planet, by Steven Dietz

One of my favorite plays is a little play written in the early 1990s at the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. It’s a story of two friends, Jody and Carl, both gay men living in an unknown, American city. It’s performed by just two actors and takes place in Jody’s map shop. Jody, a soft spoken, unassuming man, is constantly visited by Carl, an eccentric man who visits Jody’s shop on a daily basis. One day, Carl shows up to Jody’s shop with a chair. Carl, a man who often exaggerates the truth or omits the truth altogether, avoids telling Jody where the chair came from and why it’s in his shop. Carl continues to hoard the chairs in Jody’s shop and their origins become clear – Jody and Carl’s friends are dying in epic proportions from AIDS. Carl is collecting their friends’ chairs in remembrance of them.

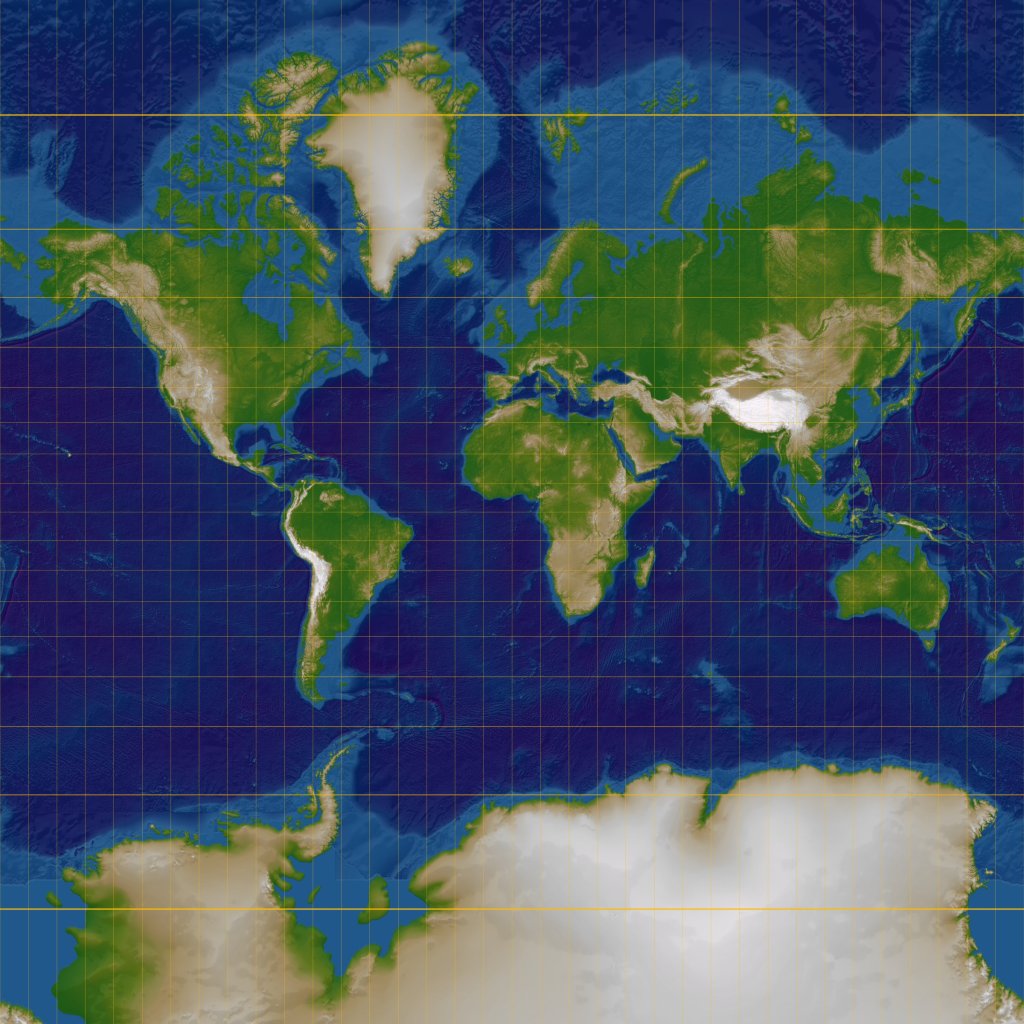

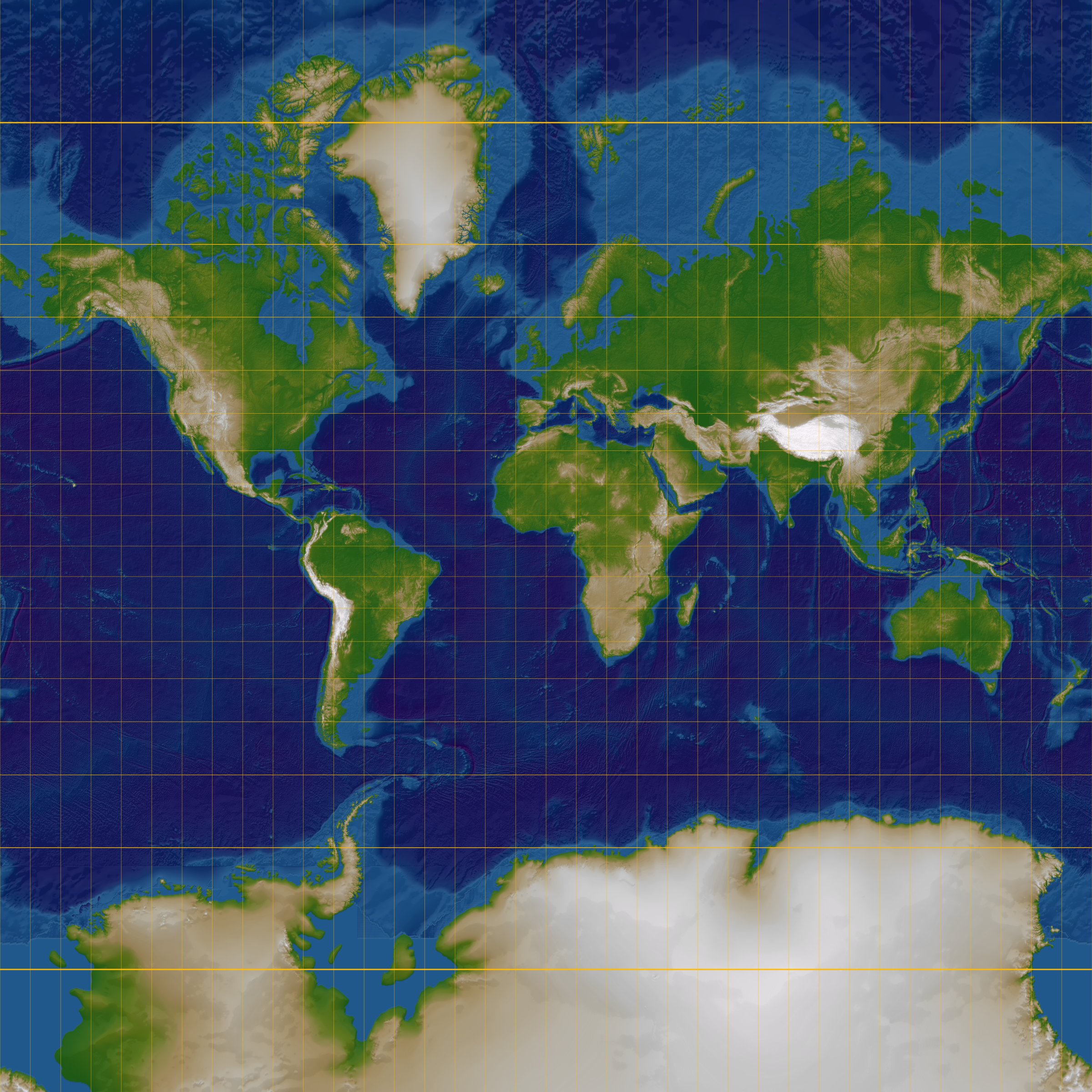

Jody attempts to make sense of the horror happening outside his shop in terms of his favorite subject, maps. He delivers a gorgeous monologue about “The Greenland Problem” and the Mercator Projection Map. He explains to the audience that the Mercator Projection Map – the one that hangs in countless classrooms around the world – inaccurately projects the proportions of the land masses on Earth. He describes what cartographers have coined “The Greenland Problem” by explaining that Greenland is actually the size of Mexico but on the Mercator Projection map it is portrayed as a behemoth country the size of South America and bigger than China. Jody also educates us by stating, “Scandinavia seems to dwarf India, though India is three times as large. And the old Soviet states appear to be twice the size of the entire African continent. In reality, they are smaller. Smaller, by oh, about four million square miles.” He tells us that Mercator drew the map in this way because it was a navigation map, designed to help sailors travel in a straight line across the oceans. Mercator never intended for teachers to use the map to teach geography. Geography as a school subject wasn’t even a thing when Mercator created the map – the map was drawn in 1569.

“File:Normal Mercator map 85deg.jpg” by RokerHRO is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

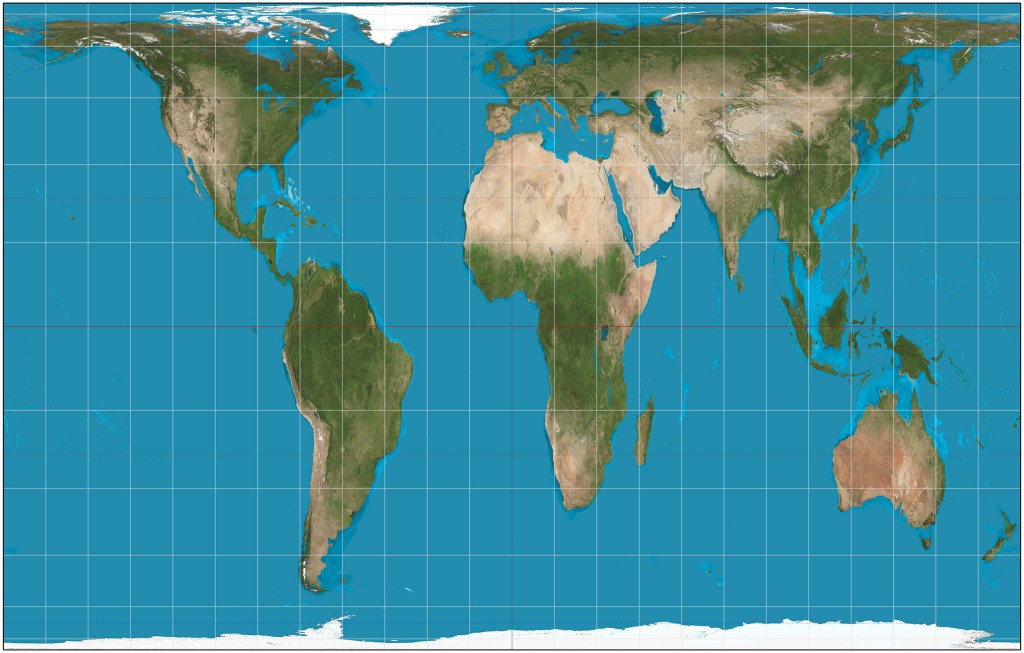

And yet, I was shocked to learn that Greenland wasn’t that big. I was the dramaturg on our production of Lonely Planet at the theater I was working at in 2014. It was my job to interpret the metaphors, motifs, and cultural references made in the play so that my audience came into the play with some context or came out with questions that I had answers to. My co-workers and many patrons were shocked as well to learn just how big Africa and South America were. And more so, just how small the United States and Europe was. I supplied the audience with the Galls-Peters Projection map (1855) – designed to display the accurate sizes of the land masses on Earth – for comparison. A shocking comparison.

“File:Gall–Peters projection SW.jpg” by Strebe is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Jody says, “A map maker takes a messy, round world and puts it neat and flat on the wall in front of you. And to do this a mapmaker must decide which distortions, which faulty perceptions he can live with – to achieve a map which suits his purposes. He must commit to viewing it from only one angle.” As his friends die around him, Jody doesn’t leave his map shop. He can’t face the truth of what is happening outside of it. He describes this as his “Greenland Problem” – his struggle to confront how is worldview has been challenged by the AIDS epidemic.

Confronting Greenland Problems Through Social Studies

I had my first Social Studies Pedagogy class this week where we discussed how everyone who comes into a social studies classroom will come in with their own biases. Those biases are the maps we have created of the world inside our minds. Like a mapmaker, we, as humans, take a messy, round world and try to make it flat and simple. My students and I will come into my classroom with our own Mercator Projection maps of the world influenced by our different cultures, experiences, and personalities.

I think it is the role of the social studies teacher to make the world a complicated globe again. To un-flatten the map and help my students acknowledge the complexities, hypocrisies, paradoxes that make up the societies that we have built. It is the teacher’s job to try to acknowledge and try to eliminate the distortions they have on their own maps when they teach. This will allow students to begin to see the world as a rounder place than their own biases have let on. It is the role of the social studies teacher to give students the information and the skills to identify what their Greenland Problem might be. It is the role of the social studies class to create a space where students can begin to confront their own Greenland Problems in a space where they encounter, communicate, and build relationships with others who have different map projections of the world in their head. My goal is not to create a unified projection of the world – this is an impossible, and I think, an undesirable, feat. My goal is to build, for students, the skills to challenge their own perspectives and consider the perspectives of people unlike themselves.

At the end of the play, Carl’s chair shows up in Jody’s shop and we learn that AIDS has taken Carl too. Jody finally leaves his map shop to face reality, at Carl’s encouragement from beyond the grave. Dietz offers some insight on how Jody solved his Greenland Problem in his Author’s Note from the play’s premiere performance in 1993. Dietz says, “Friendship, not technology, is the only thing capable of showing us the enormity of the world.” Carl’s unique perspective on the world challenged Jody’s and ultimately re-opened the world to him. Through their relationship, Jody and Carl shared their worlds with each other. I hope to help my students see how how confronting their own Greenland Problems can bring them closer into community with others who are different than them and open up the world to them.

It can be a Lonely Planet. But it doesn’t have to be, if we strive to understand each other.

– Jody, Lonely Planet, by Steven Dietz

“Apollo 17’s Blue Marble” by sjrankin is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Comment on my blog, y’all! I want to hear your thoughts!

Do you agree that one of the goals of social studies is to challenge worldviews to prepare students to have relationships with people who are different than them? Or should social studies have a more academic purpose?

What is your Greenland Problem? What or who has forced you to confront your Greenland Problem? Have you solved it? Can it be solved? For me, travelling has cracked open a lot of my Greenland Problems. I have cracked a lot of people’s Greenland Problems by travelling alone as a woman.

Who makes the planet less lonely for you?

Works Cited: Dietz, S. (1994). Lonely Planet. New York, NY: Dramatist Play Service.

Thank you for sharing this, Jenni! I love how you brought us into the experience of the play, just through how you recounted the memory of experience of it. And it’s fascinating how the map could be used as a symbol, not just for pervasive misinformation (in scale) but in how information is controlled and released (or not released) in a problematic way. I can honestly say that when I saw the title, and thought you’d be talking about maps, a part of my mind checked out. But by the time we got to the explanation of where and why the map came into relevance, I wasn’t just hooked, I was making a note to self to go down that rabbit hole of discovery because I want to know more!

LikeLike