I’m in the thick of my teacher training and I’ve been feeling overwhelmed. The demands of grad school along with student teaching and trying to maintain some sort of social life have been weighing heavy on me. I haven’t received my social studies placement yet and I’m eager and anxious to begin work in a subject that I love but frankly, intimidates me to be teaching. Which leads me to another area that I’ve been feeling overwhelmed by – the actual subject of social studies.

When I was studying for my subject test (the test required by the state of Oregon to prove competency in your area of endorsement), I often found myself laughing a manic kind of laugh at the wide breadth of knowledge I was supposed to demonstrate. It was a 150 question test that covered World History, American History, American Government and Politics, Geography, and Economics. “Ok,” I thought to myself when I made a study plan, “I just have to know everything that has ever happened in the world and how all systems of societal organization have worked and currently work. Got it. Piece of cake.” I felt like I was studying for Jeopardy.

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com

I passed the test but it was hard. I’m not going to lie. I studied for 6 months and am confident that I wouldn’t have passed the first time had not studied so rigorously. The specific dates, people, and events that I was tested on were often obscure and, I felt, irrelevant to demonstrating historical understanding or understanding of human systems. Most people can memorize a date. But I was under the impression that we had all reached a common understanding that memorizing dates does not qualify as historical study. Recognizing patterns of human behavior over long periods of time, recognizing cause and effect relationships, understanding how human psychology affects behavior and therefore a series of events, analyzing how ideas are connected and transform into tangible objects or events – this was history, right? So why was this test more of the same bad history and social studies that is taught in American schools?

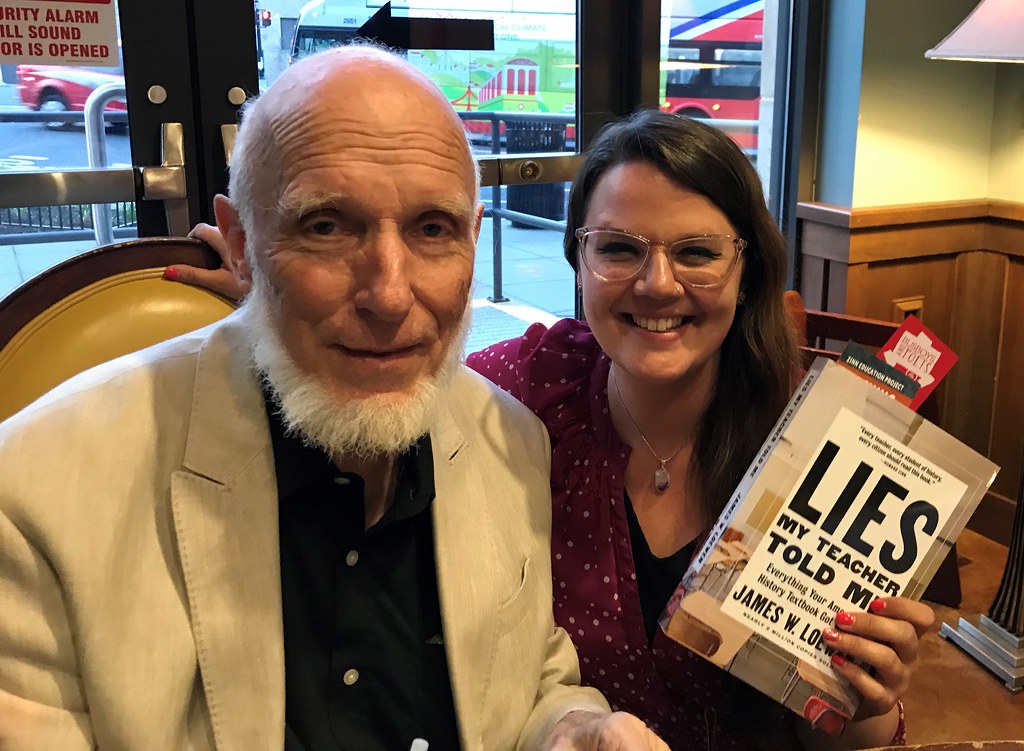

“IMG_3971” by teachingforchange is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

I took AP History in high school from an incredible teacher. While her main goal was to get us to a point where we could all earn 4’s and 5’s on the AP examine, she did her best to squeeze into her curriculum how to think like a historian. But, frankly, there just wasn’t enough time to do both. It was mostly a memorization game designed to ace a test. By no fault of hers. She had a job to do. But I got a glimpse into what history could be and it hooked me.

When I got to college I was thrilled to discover that history was different at this level. Finally, I could take a deeper dive into specific events, themes, or time periods that I just didn’t have time or the access to information to explore in high school. And to my delight, most of these classes were taught from a conceptual perspective. No more date memorization – patterns of change and continuity were the focus. I didn’t think it was possible to be more into history than I was in high school but I was. I had discovered that interpreting the past and connecting it to the present was the most interesting part of history for me. I was a conceptual historian.

High school laid a fantastic factual foundation for me to know a little about a lot of historical events and then I was able to take a deeper dive in college. But not all students are history nerds like me. The intrinsic interest isn’t there to make the hum-drum memorization game interesting or relevant. When I decided to get an endorsement in social studies, I wanted to teach history in a way that was interesting and relevant to students who would never go on to study in college or, perhaps, would after taking my class. I wanted to teach that conceptual history that college had introduced me to.

But after taking that test, I was discouraged.

Did I get the wrong impression about what being a good social studies teacher meant? Was I supposed to know history in excruciating detail? Would I be a good teacher if I didn’t? Was history still a memorization game? Imposter syndrome gripped me. Was I cut out for this?

In the sea of overwhelm, my social studies pedagogy class provided some sweet relief to my stress about whether or not I knew enough to be an effective social studies teacher. I’m not sure what we were discussing because I was overcome with overwhelm when I thought, once again, about how big of a subject social studies truly is. I raised my hand to get my professor’s perspective on how do we teach all these facts, details, dates, events, people. How do we keep up with it all? How are my students supposed to know all of this stuff if I can’t even keep it straight? I don’t know history in excruciating detail – how am I going to do the subject justice for my students? Then my professor said it.

You don’t have to teach social studies or history linearly.

Whoa.

Mind blown.

Photo by Skitterphoto on Pexels.com

This thought hadn’t even occurred to me. I’ve been so indoctrinated by the school system to think that there is no other way to teach social studies. I’ve been taught to think that the dates are the most important thing.

What a blessing it was to get the go-ahead that dates aren’t what mattered. I could teach history thematically, in an interest-based way, regionally, or in a variety of other nonlinear ways just like I had always dreamed of doing. It was such a relief to hear that I could teach my students how to think like a historian and that this was a valid way of teaching.

While the feelings of treading water in a choppy ocean haven’t quite subsided yet, this bit of news gave me a little boost of energy to keep going and to keep trusting myself. I had been onto something the whole time. A standardized test threw me off the scent – rookie move. But I’m back on track and thrilled once more by the prospect of teaching history in creative ways that expand students’ perspectives on the world and their perspectives on history itself.

This journey of studying teaching has already surprised me in so many ways in such a short amount of time. It’s got me thinking outside of the box, or in this case, the timeline. I can’t wait to see what surprise is in store for me next.

Thanks for reading!

I’d love to hear how my classmates are doing – are you overwhelmed? What things are helping stay afloat? Are you feeling like you’ve got this? What victories have you had that make you feel confident?

Does anybody else struggle with Imposter Syndrome? What tactics do you have for shutting that voice off in your head?

I love this post, Jenni! Seriously, my mind exploded at the exact moment yours did! For as overwhelmed as this whole week has been, let alone the semester, hearing that put things back into a whole new focus that got me excited again!

LikeLike